Last year, I took the FMS online certification class and it left me wanting more information. Screening someone for imbalances is fine, but what do you do with them afterwards?

Getting some corrective exercises prescribed to me was great, but I didn’t have a great idea on how to prescribe correctives to someone else via their results of the screen. I spent a ton of cash on DVDs and materials from Gray Cook but still I felt there was something missing.

This is why I leaped on the chance to take the FMS Level 1 and 2 certification when it finally came to SF. And also, it was being taught by Dr. Mark Cheng, renowned martial artist, Sr. SFG instructor, and proponent of the FMS. I have been a big fan of Doc Cheng’s for a while now, after I started on my path to the SFG Level 1 certification. Now I would get the chance to meet him live and hear him teach the FMS.

I took both the FMS Level 1 and 2 even though I already was certified in Level 1 via the online system. I didn’t want to miss Doc Cheng’s lecture on the first part – hearing it live versus in online materials is much better and it constantly evolves, so I would get the latest information that weekend. FMS Level 1 teaches the screen only, and FMS Level 2 teaches the corrective exercises. So to me, knowing the screen is great but less than half the battle; most of the work happens after the screen in making the client a better athlete.

It was more than I hoped for! Now I had the templates and methodology to apply corrective exercises in a systematic way to correct an athlete’s imbalances which were sorely missing from just taking the FMS Level 1 course! The general path to treating a client goes like this:

1. Identify the imbalances via the screen

2. Mobility

3. Static motor control

4. Dynamic motor control

5. Strength and conditioning

You screen someone and determine their most critical imbalances; then you go through each step in order, making sure that the client has achieved a basic level of each step before moving onto the next. In our course, we are given a ton of corrective exercises, most of which are found at Functional Movement website. Without taking the course, these exercises were all a big jumble. Which ones should I apply and when? Which one should I do first? How do I know when something is working? All these were outlined in the course.

Learning the screen in Level 1 is great, but without Level 2 it is almost pointless. I highly recommend taking both together and not just online but live in front of a lecturer. Doc Cheng was awesome and I hope to hear him again, as well as someday Gray Cook and Lee Burton the creators of the FMS soon.

Category Archives: Injury Prevention, Recovery, Healing, and Performance Enhancement

The Functional Movement Screen, Corrective Exercises, Movement Patterns, and Fixing Me!

A while back, my sports med doc put me through the Functional Movement Screen or FMS. The FMS is a set of 7 physical tests, designed to capture movement imbalances between your left and right sides. Research has shown that movement imbalances are a great predictor of potential for injury. With the FMS, trainers and clinicians now have a tool to measure athletes’ imbalances. But there is more: the FMS system includes a set of corrective exercises which are designed to be used from the results of the FMS. The whole system is very templatized; you don’t need to think about which corrective exercise to use but simply employ the progressions depending on the results of the test. Another big advance that the FMS makes is that it attempts to treat imbalances via movement patterns, not individual muscles. Traditionally, clinicians would attempt to exercise individual muscles when addressing problems.

These few sentences above do not do the FMS justice; the founder Gray Cook has better discussion on his site FunctionalMovement.com.

When I took the test, I didn’t really do any of the corrective exercises and didn’t fully understand the purpose of the FMS. Recently I started digging deeper into the FMS and what its full purpose is. I bought a ton of the FMS DVDs from Perform Better and went through them all. I realized that here could be the answer to nagging athletic problems that I’ve had through the years! For example, I have a tendency to cramp in my inner right quad by the knee on marathons – I have tried everything to cure cramps: electrolyte/salt tablets, strength training, more training, different types of training – nothing seemed to cure it. Each year I would race a marathon and inevitably no matter how hard I trained, or how many salt/electrolyte pills I would take, I would still cramp in the latter half of the race.

However, now the FMS has given me more clues at to why I might be cramping and why all those other reasons could never completely cure it. It has to do with muscle imbalances which cause me to compensate for poor movement patterns, and these muscles used in compensating eventually wipe out before the end of the marathon, causing me to cramp up.

Or at least that seems to be the theory. Certainly there is nothing left to try!

I got tested via the FMS again from my sports med doc. Then I got a series of corrective exercises to employ from the results of the FMS. For the last 2 months, I’ve been doing them multiple times a week. Although I have not retested my running again, I’ve noticed some interesting results:

1. My core control is not optimal in the push up. Working on this allowed me to correctly tense up my entire body so that when I push up, my body comes up as a single unit, with no body part lagging.

2. My left/right balance is very uneven. I have a tendency to always lean to the right, even when balancing on my left leg. I worked with some Gray Cook Bands on my one leg stance:

The other thing that helped my left leg balance was the use of a technique called Reactive Neuromuscular Training (RNT). I used a Gray Cook Band on my left knee, pulling it inward into a “mistake” which is called Valgus Collapse. When the band pulls my knee inward, my body relearns how to stop my knee from collapsing inward, firing the right muscles. So I did rear lunges and high steps onto a 12″ surface both with the band pulling my left knee inward. After a few weeks of this, this really helped my balance a ton. Before this, I would step up 12″ and I would wobble like crazy and then tip to the right. After doing this for a few weeks, I could step up now with decent balance.

Both have improved my ability to balance on my left leg.

3. A surprising result was when I was trying to improve the stability of my core in a quadriped position. There is a drill which is called Rolling Pattern.

You have to roll back and forth with one elbow touching the opposite knee.

When I did this, my right side, or right arm extended above my head, was fine. However, I had major problems with my left side, or left arm extended above my head. I worked on this for a while and finally got the hang of doing it with left arm extended.

This had an expected result in improving my swimming. I had been having a lot of trouble with my left arm spearing forward/right leg kicking in two beat kick. I could not generate the same amount of my propulsion when spearing with my right arm forward. The coordination had eluded me for months until I did this drill and got better at it. All of a sudden, I was experiencing much better propulsion on my left spear! This Rolling Pattern had somehow awakened the right core activation to initiate the right movements in the left spear action.

4. I also discovered some pelvic control issues in the active straight leg raise while lying down. To help with this, I used a Gray Cook Band to improve my core engagement while raising one leg at a time while lying down:

At the moment, I am working through some corrective exercises with the kettlebell. Gray Cook created a special FMS system that is designed with kettlebells called the CK-FMS. There are a number of great corrective concepts coming out of the kettlebell community and I am going through those one by one. One of my favorites is Kettlebells from the Ground Up 2, whose drills showed that I still had poor pelvic control in a straight leg raised position. For me, I am going through those to activate the right stabilizing muscles while swinging a cannonball with a handle on it – definitely taking some time for my body to figure out how to do that right and without messing myself up!

As a result of all this, I got certified with the FMS Level 1 a few months back. This allowed me to administer the test but I was still missing the critical FMS Level 2 which was the set of corrective exercises to give as a result of the test. I am looking forward to that this coming March in SF with the infamous Dr. Mark Cheng, one of the most knowledgeable folks in the field.

As I learn to become a personal trainer, I find that the FMS is a critical part of the equation. Gray Cook is fond of saying that he refuses to train people unless they get a minimum score on the FMS and that left and right sides of an athlete are equally balanced, or equally inbalanced. I think this is one of the most important concepts missing with personal training today, which is both an issue with trainers and with clients. Clients are mostly at fault because they just think they can go out there and train and race, regardless of their physical condition, and have no patience for doing something else. Trainers need to build a business, and clients who want to leap into training immediately often will leave trainers who don’t start immediately and recommend something else.

As a guy who has experienced first hand what can happen to an unbalanced body, I wish that someone could have put me through the FMS system before I started training for triathlon. Those corrections would have balanced my body and then could have made my racing career much less injury prone, perhaps even removing cramps during my marathons.

I look forward to continuing corrective exercises on myself, and also the FMS Level 2 course coming in March to the SF Bay!

Some other interesting observations as a result of this process and things I’m looking into:

1. I learned about mechanoreceptors on my feet and how important they are to activating the right muscles during walking and running. If they do not get the proper stimulus, then my movement pattern for walking/running can get totally messed up. I also learned that this can extend up to the ankle as well, so loosening up the ankle through dorsiflexion exercises as well as releasing tension in the feet can make a huge difference in how you perform during a workout.

2. Evaluating the difference between the left and right sides for the active straight leg raise whlie lying down can show problems in running. If one side is more restricted than the other, then the length of my stride will be different on each side, which can cause compensations and other problems when my body tries to use other muscles and body parts to equalize my stride.

3. I’m building up my spinal stabilizers, which still aren’t firing correctly. This is critical not only for the Deep Squat, but also for improving my Deadlift and maintaining proper back position during heavy kettlebell swings. Many FMS corrective exercises involve helping my spinal stabilizers to fire properly again. This has helped greatly in my deadlifting and achieve my goal of 2x body weight.

4. Maintaining proper back alignment has many more critical effects than I could have imagined.

5. Been reading up on the Janda method for correcting muscle imbalances (see Assessment and Treatment of Muscle Imbalance:The Janda Approach). Fascinating stuff!

6. Equally fascinating are the methods pioneered by Alois Brügger in Switzerland for postural correction. Very related to FMS corrections.

7. The master of backs is Dr. Stuart McGill. More stuff to dig into.

8. It also has made rethink gluteal amnesia and what it means to treat it. While glutes being weak and not firing is a big problem, they can’t only be trained in isolation as a muscle group. Merely getting them stronger and firing again doesn’t mean they will fire properly in the right sequence during movement. Again this is where FMS corrective exercises come into play, and retraining the body for proper movement, potentially starting from infant based movements on the ground to standing up.

9. Along with 8., I find the concept of not strengthening stabilizers to be eye opening. This is what therapists did before. If you injured a stabilizing muscle, they made you do weights or reps with that muscles, thinking that’s what would make it work properly again. But this is only half the equation; rehab-ing it may require manual manipulation and some training to get it functional and pain free, but it doesn’t mean the nervous system is going to fire it properly during movement.

10. This is my big learning after 9. Pain and injury can cause your nervous system to compensate and remove proper movement patterns, replacing them with patterns that will allow you to complete the movement but with the muscles and structures that weren’t designed to do it for long periods of time. Some of these movement patterns need to be re-patterned back after injury and pain.

11. Central nervous system training has come to the forefront of my mind in my own training.

ART for Swim Performance Enhancement

Way back in 2005, I wrote about how Active Release Technique (ART) could be used for performance enhancement in my post, Where there is Pain, There is Gain… . Using ART, I released decades of adhesions that were restricting my hips from moving properly. After loosening of them up, I was able to improve my speed dramatically in as little as two weeks!

This last week I asked my ART doc to check out my shoulder blades or scapulae due to a new focal point I learned through Total Immersion. This focal point was to move the scapula forward during arm recovery, so as to increase the elbow’s forward position during a proper elbow led recovery. As I practiced this, I became aware that I was performing an unfamiliar movement, and I immediately thought of using ART to make sure that my muscle structure around my shoulder blades remained loose. If they were tight and short, then those muscles would restrict the movement of the shoulder blade forward and either not let it get as far forward as possible, or start using too much energy in the muscles used in moving the shoulder blade forward.

My ART doc did some work on the muscles of the shoulder blades. The muscles that could restrict the movement of the shoulder blade forward are the rhomboids, erector spinae, lower trapezoids, and serratus anterior. Strangely, my left side was worse than my right; certainly there were restrictions there, but the left side was much more restricted. Once he released those muscles, my shoulder blade did feel looser.

However, in thinking further, I think this is correct – my left side does have a better elbow led recovery than my right, and it’s possible that this action did naturally cause more restriction in those muscles. Now I’m trying to even it out and so I anticipate more restrictions to pop up as I perform this unfamiliar movement. Still, with constant ART treatment, I should be able to fully integrate the correct movement for elbow led recovery while managing my muscles’ adaptation process. Without ART, I run the risk of letting the restrictions and adhesions grow, which could cause injury and movement issues later on.

ART is an amazing discipline and I enjoy exploring its performance enhancing capabilities in my training.

Muscle Cramp Update

In my experience, cramping is caused by at least 5 factors that i’ve encountered. these are:

1. Strength – lack of strength in your muscles means they are faster to tire and cramp up due to lack of ability to keep up with your demands of the muscles.

2. Fitness – poor or lowered fitness in that activity or overall can cause cramping as muscles unaccustomed to an action are forced to do that action repeatedly.

3. Overworked muscles – muscles that are pushed beyond their ability to keep up will inevitably cramp. This can be either a function of 1 or 2 above or something more non-obvious like your nervous system not working right to make all your muscles in a kinetic chain fire off in the right way or at all. This will put more stress on the muscles that are doing the work versus ones that are shut down. The glutes are a typical muscle group that has shut down due to inactivity of sitting, which overworks the back erectors and hamstrings when running and squating.

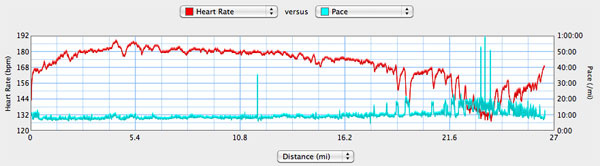

4. Not enough blood/nutrients getting to your muscles – this can happen in situations like windsurfing in cool seas where hypothermia starts to set in and your muscles simply stop getting enough blood flow to function properly. I encountered this during the LA Marathon 2010 when my right quad cramped up under rainy, cold weather. I thought it was lack of strength which may have contributed in general, but an examination of my heart rate trace showed a slow drop in heart rate, which meant that not enough blood was getting to my muscles while I was demanding so much from them during a race.

5. Electrolytes – you may not have enough electrolytes in your system to support that level of activity, or through sweating and hot weather racing/training you lose it through the skin and it is not replenished. electrolytes are important for proper functioning of muscles and the nervous system. Without proper levels, you will undoubtedly cramp. I sweat a lot, more than other people, and I take 3 Saltstick pills per hour during Ironman races in moderate warm to hot weather. This has become more of a preventative measure now as my strength and fitness has increased.

Science has not been able to pinpoint the exact causes of cramping but suffice to say that training over the years and trying many things, these are things that I’ve worked on the most and have nearly removed cramping situations, except for the extra cold, wet conditions experienced during the LA Marathon 2010.

My latest experiments have been in the area of increasing strength (but not bulk or weight) via Russian strength training techniques in benchpressing and deadlifting. Another has been in the area of recovery between intervals, relative to my fitness level. I have found some great results in training intervals with full recovery in between them, versus trying to use set minimal recovery intervals in order to build endurance. The last has been in the area of removing “gluteal amnesia”, which is getting my glutes to reactivate in the kinetic chain involving running. This has all but removed issues with hamstring cramping and I have also improved my running speed as well.

Deadlifting is HARD (and Dangerous)

Well, my first adventures with the deadlift were enlightening and a bit painful.

I was foolishly naive about the details of deadlifting form and just started into deadlifting without thinking too much about it. I only thought to keep my back in neutral position and then lift the weight. I started by trying the prescribed path in Underground Secrets to Faster Running by Barry Ross which suggests a series of weights to try in order to determine my maximum weights at certain repetitions. It starts at 50% of my body weight and works upwards from there, until you find your one rep max, or 1RM.

I got up to a rather wimpy 195 lbs for 2 reps and then trying 215 I could not budge it at all! This unfortunately strained my back, probably both muscles and my spine, for several days. I then had a session with my physical therapist who ran me through the intricate details of deadlifting form. In fact, around 155 lbs my upper back started to curl and my shoulders could not be kept in position as the weight dragged my upper body down. I should have realized this and not kept going.

I found out that deadlifting is more than what it seems. At first glance, it seems to be just a leg building exercise but it actually builds the entire upper body as well. You need to be able to activate a sequence of upper body muscles to not only lock the spine into neutral position but also to be able to perform the lift and get the weight off the ground and up into its final position.

I found out the hard way that I didn’t have the ability to activate my muscles in the right sequence, and also some of my muscles had “amnesia” which meant that my body had forgotten how to activate them when I needed their help in making the lift. This was a problem that had been plaguing me for my running – I know I have “gluteal amnesia” where my glutes would not fire and my hamstrings would get wiped out from running and ultimately cramp up during a race.

But first, the proper sequence, for the sumo version:

1. Take a wide stance, similar to the initial setup position of a sumo wrestler. The feet should be pointing about 45 degrees outward from center. Take as wide a stance as your flexibility allows; this will allow you to get the grip on the bar of the barbell as close to your body’s axis as possible, which allows the body to take the weight of the barbell with the spine as vertical as possible.

If you can, lift barefoot or in Vibram Five Fingers. Even the height of the sole can cause instability in the lift.

2. Push your shins up to the bar, touching it. You will want the feeling of scraping the bar up along the shins when you lift up, but also being that close to the bar means the weight is as close to your centerline as possible.

3. Squat down. The flexibility of the leg and hip muscles may prevent you from getting down really low into a low squat, but you want to get as low as you are able. Also, you may find that your muscles are not strong and/or activated enough to be able to lift weight from such a low starting position. You may need to start in a higher squatted position.

4. Hinge the hips such that your butt is sticking out and not curled underneath. If your butt is curled under your spine, that means your spine is not aligned near the bottom which is bad. Lots of bad pressure to your disks if not aligned!

5. Grip the bar. Use opposite grips with the hands, one with the palm facing inward and one with the palm facing outward. With the hands in opposite directions, you can actually lift more.

6. In preparation for the lift, do this:

a. Grip the bar firmly.

b. Load up to right before the lift by extending upward with the body, but maintaining a neutral spine.

c. In loading up, tighten up the core, the back muscles, and the shoulder muscles. This will lock up the body in position and prevent your back/spine from moving out of alignment which will increase the possibility of injury.

d. Grip the ground with your feet and press up to right before the lift, flexing the leg muscles and glutes.

e. Look up at about a 45 degree angle. This will help keep the body in alignment. Looking down could cause your body to curl.

Setting up for the lift is super important. You want to make sure your whole body is locked in for the ultimate effort to lift the weight off the ground.

7. Take a deep breath and hold it. Holding your breath during the lift will help get you maximum effort. Then, as if you’re going to force your feet/heels through the ground, press the weight up, rising up on your legs, while keeping your body locked from step 6 above.

8. When you reach full extension of your legs, expel your breath at the top of the lift. Pull your shoulders back slightly, and then shove your hips forward while flexing your glutes. This completes the lift.

9. While the books prescribe dropping the bar, this is nearly impossible in most consumer gyms. You have to be at a real muscle place like Gold’s Gym to be able to drop a heavy weight without people or the staff complaining, or even if the floor can take that much of a weight slamming down on it from knee height.

Instead, after expelling your breath, take another breath, lock your body into position and then slowly lower the bar with your legs back to the floor.

10. Repeat steps 1-9 until you finish your set.

Now I practice this with only 135 lbs. Over the last few sessions, I make sure I can do this absolutely right. It is an interesting muscle activation experience.

When I lift, I rehearse the sequence through my brain as it’s easy to just forget one of the steps if I move too quickly.

I must maintain control and flexing of a whole set of muscles during the lift. I find that if I lose concentration, I can lose the tightening of any set of muscles which lock my body into position. This is bad and can cause my back to be sore, or cause my disks to fire up other muscles like my hamstrings, glutes, or erectors (back muscles).

Early on, I could feel that certain muscles just weren’t firing at all, especially my glutes. I could tell because after the workout, my hamstrings were very tight. Now I also focus on flexing my glutes especially during the lift.

I also have to watch the floor. At the YMCA in NYC, the floor is a rubberized tile. But it is also slippery against the soles of my running shoes, which caused my left foot to slip outward during a lift – very dangerous. I finally just took off my running shoes and socks and lifted barefoot. My sweaty feet nicely gripped the otherwise slippery tiles.

I need to burn the entire steps 1-9 into my brain so that I do it all, in sequence, naturally and every time.

Once I get the steps into my nervous system, then and only then can I start increasing the weight I lift.

Other exercises that are helping:

1. Cable rows, pulling the weight with elbows low.

2. Using a functional trainer or similar (one of those things with weights and cables and adjustable big arms), I row low, pulling my elbows to my sides and then pull my arms downward for triceps extensions.

3. Single leg dumbbell deadlifts, great for glute activation.

4. Single leg supine hip raises, one leg at a time.

Such a simple looking move, but yet so complex! I look forward to advancing in my Russian strength building techniques, and hopefully my running as well.

NOTE: By the way, an amazing back book is this: Ultimate Back Fitness and Performance by Stuart McGill. It’s expensive but well worth the read.

LA Marathon 2011 Post-Mortem and Recovery: 3-21-11

Recovery is going pretty well. I took about 70g of protein powder after the race, through many doses across the rest of the day. Today, race day + 1, I took an additional 80g of protein powder. Both days I drank several packets of Emergen-C to keep throwing vitamin-C and other essential vitamins into my body for recovery.

Currently, after the race, what hurts:

1. My left ankle, but after I adjusted it, the pain went away!

2. My left anterior tibialis is sore. Left ankle area on top is sore when I move/bend the foot.

3. My right anterior tibialis is not sore much. Right ankle area on top is sore when i move/bend the foot.

Re: 2 and 3 – I think that the numbness in feet due to cold contributed to this. I felt like I was running on club feet and could not tell how my feet were landing on the ground. This could mean that my foot contact was not optimal and beating up my ankles and the surrounding structures more than normal.

4. Almost no soreness in either hamstring or glutes. I think those 4 Hour Body exercises are working well!

5. Both quads very sore. I think this was exacerbated by the cramping in both quads. I suspect 3 things that caused the cramping:

a. It was a cold day and I was not drinking much, so less electrolyte contribution from my sports drink. I was gel-ing every 45 min. so that was still on my normal schedule. I had electrolyte tablets with me, but didn’t take them until mile 14 after my right quad cramped. By then it was too late. I should have started taking them on my usual schedule, but I was also curious to see if I really needed that much electrolytes, and especially on such a cold day.

b. The cold was driving down my heart rate. I looked at my HR graph from my Garmin 305, and it steadily declined as the day wore on. Some of that was due to my walking, but I could see my HR angling downward even before my first cramping at mile 14.

So I wonder about whether or not less blood flowing through my muscles caused the cramping since they were not getting enough nutrients or electrolytes. Need to look up research on the effect of cold on muscles and cramping.

c. I’m just not strong enough. After I recover, I’m going to start on some suggestions in the 4 Hour Body book from the coach who makes sure his athletes are super strong for running, using lots of deadlifts and similar exercises. I think I’m pretty weak in the quads, and especially if I’ve been working the hams/glutes with the weights/exercises I’ve been doing and they have practically no soreness at all.

5. My right shoulder/pec is very sore. It was getting sore towards the latter half of the race. I suspect that carrying my kid too much had something to do with that. It was taking a lot of my concentration to keep that shoulder/pec from tightening up as I ran.

6. I only slept 4 hours the night before. Every night before that, since daylight savings time started, I have not gotten really good nights of sleep at all. So a whole week of not sleeping enough may have left me at not maximum condition at start of the race.

Lots to think about and work on in the next upcoming months.

The Vitamins and Supplements I Take Every Day

I thought I’d post all the pills, vitamins, and supplements I take every day. Here they are:

Moxxor Omega-3s (4) – Highly concentrated Omega-3s with no fish burps, made from shellfish.

New Chapter Probiotic All Flora (2) – Proper care of friendly bacteria in the digestive tract is supposed to ward off diseases of all sorts.

Vitamin D3 2000IU (1) – Doctors say we’re low on D in general.

Solgar Gentle Iron 25mg (1) – Blood tests showed me low on iron, and important for oxygen transport for us athletes.

Nordic Naturals Ultimate Omega+CoQ10 (2) – More Omega-3s, but with CoQ10 which helps performance and recovery.

Whole Foods Vitamin C 1000mg (1) – Sickness prevention FTW!

Whole Foods Ginkgo Biloba 60mg (1) – I’m not getting any younger, my brain can use any help at all!

Whole Foods High Potency Multi (1) – A whole lot of all vitamins.

Whole Foods B Complex (1) – Supposedly helps the fat metabolizers (see below).

First Endurance Multi-V (3) – A special mix for athletes, plus some herbs to enhance performance.

First Endurance Optygen (3) – Tibetan monks nibble on these herbs to increase their ability to endure the high altitudes, supposedly increasing oxygen utilization.

In addition to that daily cocktail, I started supplementing based on Tim Ferriss’s book, 4-Hour Body, which are supposed to enhance one’s fat metabolism. With every meal, I take:

365 Garlic 500mg (1)

365 Alpha Lipoic Acid 100mg (1)

Now Green Tea Extract 400mg (2)

And then, at night before I go to sleep:

Jarrow Policosanol 10mg 2 (2)

365 Garlic 500mg (1)

365 Alpha Lipoic Acid 100mg (1)

Does all this stuff work? Who knows for sure. I do know that the 4 Hour Body supplements have been making my fat content drop because I do measure it. But as for the other stuff – “that which does not kill me, must make me stronger”…right?

Resting Heart Rate, Recovery, and Subsequent Performance on that Day

3 weeks ago I purchased a Finger Pulse Oximeter OLED Display to use in the mornings to record my resting heart rate. I have found that using this little device is a lot easier than lifting up my shirt and putting my normal HR strap on and then taking a look at my watch. I just slip this on my fingertip and turn it on, and then try to relax as much as I can and take the lowest reading that maintains some steady state. Minimal movement is key here, because once you start moving around, your base HR increases. So I want the lowest HR reading possible, which I can achieve my slipping this pulse oximeter on my finger and taking a reading.

A while back, I had learned about taking resting heart rate readings in the morning and using that as a measure of how recovered I was. I’ve been doing this for about 3 weeks now and the results have been enlightening.

My usual, fully recovered resting HR is about 58. If I can get a reading that low, then usually that day I can have a pretty decent workout. On the days after my long runs, I can usually only get a reading of 62. I also know, by the soreness in my legs, that I am not fully recovered. So a mere increase of about 4 beats per minute is enough to signal that I am not fully recovered.

These last few days have been really interesting. Yesterday, I measured my resting HR and found it was 66! No matter what I did, trying to relax all tension in my body, breath slower, etc., I could not get it lower than that. Then I went out to run an 18 miler, but pooped out only after 12 miles: my effort to maintain pace was increasing, my mind’s focus was dwindling, my thighs were also getting more tighter than usual. So I finally stopped on my 2nd 6 mile loop and called it day.

In analyzing what could have caused this, I looked back to the day before. I had an ART session, which I have seen in the past can hamper a workout because ART does cause actual trauma to the muscles and vigorous ART sessions can have a detrimental effect on performance in the short term, even as it helps healing and recovery in the long term. I also had an extra large glass of red wine, and these days I’m not drinking much so alcohol has been hard to purge from my system, even at amounts as low as one glass. Perhaps the biggest issue was that my son had trouble sleeping, and I’m pretty sure I woke 4-5 times in the night due to his crying. Interrupted sleep does not have a good effect on recovery!

This morning, my resting HR was 68 – even higher than yesterday! Looking back at the night before, I had a large glass of beer at dinner, I was wiped out from running 12 of the 18 miles I wanted to run, and then last night my son would not sleep from 130a to 400a and of course my sleep was disturbed multiple times. I was going to go for a swim, but just decided to take the day off.

Very interesting results tracking my morning resting heart rate. Now that I’ve started, I’m not going to stop as I’ve seen the useful data it provides.

Pain in Training and Racing

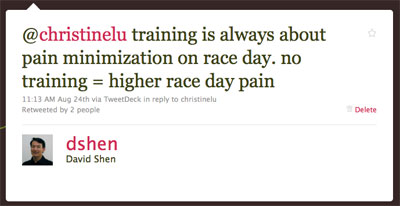

Last week I tweeted that to a friend whom I’ve been helping with her marathon training. It sparked a whole bunch of thoughts about pain and its role in training and racing that I’ve been thinking about a lot over the last few years.

1. Pain kinda sucks.

2. Pain can be physical, mental, and emotional. It can also emcompass more than one of the three, or all three.

3. We can build tolerance for pain through training. Through progressive experience with pain, we can raise our threshold for it.

4. Pain can and will stop us from doing whatever it was we were doing. It is a natural defense mechanism that tells us that we have reached some limit and that crossing that limit is a dangerous thing, and that we should back off.

5. There are two kinds of pain: that which is just experienced but is not a result of physical harm or injury, and that which comes with true physical harm or injury. Many times it is hard to distinguish between the two. But I’ve learned that through experience, we can raise the probability that we can distinguish when pain is telling us something bad has happened and when it is just a sensation. With 6 Ironmans under my belt and 8 years of triathlon training, I think I’ve gotten fairly good and knowing which pain is which when I experience it.

I say “probability” because I’ve found that sometimes I still diagnose a pain sensation as not the result of harm when it actually is. This is most often the result of us athletes attempting to train hard and to train through pain.

6. No matter what, pain is sending you a message. It is always worthwhile to analyze and diagnose why you were experiencing pain.

7. Generally, if you don’t experience pain during training, it means that you’ve adapted to the level of stress you’ve been putting your body through. To increase your performance, you have to add stress beyond where you are now; often this comes with some level of pain.

However, you don’t have to add significant amount of pain to improve. Inching your way up is much better than trying to ramrod fitness improvement. You risk injury and overtraining if you try to ramrod.

8. Many people (and their old school coaches) think that you have to push to the limit every single time in order to improve. No Pain No Gain is their motto. The problem with that is that they ignore when someone’s injury threshold has been crossed, as they are trying to improve their pain threshold. They heap abuse and negative motivation at you when you collapse, thinking that you have wimped out. That may be the case, but they unfortunately also have no ability to recognize when true injury happens and when to back off.

The reality is that the body needs to recover. Young people recover sooner than older people. Even within an age group of people, individuals will have different recovery speeds. When the body is subjected to overwhelming stress, it will attempt to adapt. In fact, it may improve for a while. Then some limit happens when the body cannot recover quickly enough to deal with the next overwhelming workout. Injury occurs, or worse, we enter an overtrained state which requires month of rest to pull out of.

Current research has shown that a measured and orderly approach to adding stress, even what I would call overwhelming stress, can safely progress an athlete to the best performances of their lives. It’s too bad that most people don’t know this. Generally it’s best to avoid training with people who still think that way.

9. As my fitness has increased, and my tolerance for pain has increased, my experience of pain has changed for pain which is not injury/harm related. It has transformed itself into more of a rising discomfort level in the body to maintain a current pace. Mental pressure increases and my brain wants to back off on the effort. However, I only flirt with this at the edges of maximum effort. Physically, I feel it in the lungs as my breathing becomes more heavy. I rarely feel burn in my muscles however; instead, I feel rising tightness and tiredness, an inability to maintain/increase effort no matter how hard I will it.

I think that other people characterize this as a type of pain sensation, but I don’t experience it as a pain anymore.

Thus, it has become a battle for stamina, and where tempo and threshold training really becomes important for the latter parts of races where diminishing resources compete with rising effort to get to the finish line.

10. It is well documented that all serious Ironman competitors experience a lot of pain in races because they are giving max 100+% effort the whole way in order to place high in the rankings. You have to know how to dig deep and ignore any pains in your body to do this.

My coach M2 has told me that he trained his body to go within 2-3 beats of his lactate threshold heart rate the whole race. That’s pretty tough to race like that; racing too close to your lactate threshold heart rate for too long can cause a flame out. On the other hand, M2 has won Ironman Canada and was a serious professional Ironman contender for many years.

So this kind of level can be attained through training and practice. It is not enjoyable practice, but achievable if one puts their mind to it.

11. Now we return to my original tweet. To me, training is very much about pain reduction on race day. The better trained you are, the better prepared you are for the race and what convolutions race day may throw at you.

Some things that can happen:

a. You want to get a personal record, so you push hard. However, if you don’t train to race at a certain pace, you could flame out or bonk well before the finish line, which causes pain in the form of cramping or wiped out, tired muscles, or mental/emotional frustration because you can’t run as fast as you started and thus disappointment sets in.

b. Related to a., you set some time goal and then set out at that pace, thinking to maintain it the whole way. However, if you don’t train correctly, you could find that you went out too fast and then somewhere around midway your speed starts dropping and you can’t maintain speed. Again, this could lead to muscular and mental pain.

c. Normally races start in the morning, sometimes pretty early. Ironmans usually start at 700a, the Honolulu Marathon I will race later this year starts at 500a. Why? Because as the day wears on, the sun rises. The temperature also rises as well and it may be in the low 50-60s in the morning but may get into the 90s. For example, a buddy of mine told me at Ironman Louisville this year, it was 75 degrees at 700a and rose to 95 degrees by midafternoon: a brutal race for those who have raced Ironman in those conditions.

Some people think it’s cool to kind of meander through the race casually and think it’s going to be a great experience. I can tell you that after 6 Ironmans under my belt, that the more time you are out there, the worse it gets…period.

The longer you are out there, the more your personal resources get used up, both physical and mental. You may even lose the will to keep going, and the probability of you quitting just grows. As the sun rises, the ambient temperature also rises. Believe me it is a different experience racing in 60, 70, 80, or 90 degree weather. Faster races always happen with cooler temps; your body doesn’t have to work as hard trying to cool itself. Your body will use up water and energy to cool itself at higher temps, which could have been used to propel you but instead is used up sweating. In many Ironmans, the wind tends to pick up also later in the day, so if you’re still on the bike, this just gets worse and worse as you fight wind and declining resources to get to the finish line.

Other things have happened, like aid stations will start running out of fluids and nutrition. At Ironman Austria in 2006, at the last moment they let in a few more hundred people, which resulted in aid stations on the bike running out of both fluids and water bottles to pass out as the temps reached the mid-80s midday. I wasn’t the slowest but even when I hit the last 2 aid stations they were already out of water bottles. I can’t imagine what it was like for people after me.

As the race progresses, there is a high probability that you will slow down. So now that you’re slower, the time between aid stations grows. You’re still sweating and getting tired, but can’t get the next batch of fluids and nutrition for a longer period of time, and you need it more now. Great.

One of my main mantras these days is to get faster and to do anything it takes to get faster. That means training smarter, not necessarily harder, but with a focus on improving fitness and speed. It’s all about doing the right things to get to the finish line as fast as possible as I know that the longer I’m out there, the more the potential I’ll have a bad experience.

To me, training properly has a lot to do with pain reduction during a race. I would much rather experience smaller bursts of pain over the course of training for a race than getting to race day and experiencing it there. Preparation in the physical, mental, and emotional aspects are all important in having a great race but if you don’t put in the time and effort beforehand, I guarantee you that you could have a miserable experience out there on the course.

Belly Breathing

A long time ago in Bicycling magazine, I saw an unflattering side shot of Jan Ullrich at the Tour de France showing his belly jutting out. It was, however, an article on breathing from the diaphragm and how it gives you added ability to get more air into your system. The Jan Ullrich picture was not illustrate that he had developed a beer gut, but rather that he was showing a more effective breathing method. Here are some pics of Lance Armstrong on this post from CyclingNews Forums notice how low his belly hangs. He’s also a master of belly breathing.

This came up again just recently for me. I am attempting to build for the Honolulu Marathon at the end of the year right now and just completed my base phase, after about 2 false starts due to having a baby this year and also a nasty allergy attack which set me back about 2 weeks. Previously this year, I had gone out twice to see if I could complete my usual track benchmark of 10x400s RI 1:00. But for some reason, I would seriously wipeout at about 4 400s. I tried both running a little aggressively, and also then tried the second time at a more conservative pace. But no dice. I would get to 4 laps and wipe out.

This was very wrong! In years past, I could always complete my benchmark workout. But this year, I think there was a big difference. This was the fact that I was doing a lot of neuromuscular training on the treadmill. My nervous system is now primed to moving my legs faster than in previous years which is great, but it is unknown how long I can maintain a faster pace since these workouts tend to be a minute maximum with lots of rest, and are more for getting my nervous system used to moving my legs fast and not using extra energy to do that.

So when I hit the track, I was just moving my legs faster given that my nervous system was now OK with that, but I think I hit an upper limit to my lung capacity given the way I was breathing.

All right: I admit it. When I’m out there, I tend to suck in my gut to make myself look better and not like I have a fat belly. But I think this has created an artificial upper bound to my lung capacity because it doesn’t allow me to fully engage my diaphragm when I breathe.

Thus, on previous attempts this year, I would run faster 400s which is good, but wipe out a lot sooner as the oxygen in my system got quickly used up due to running at a faster pace.

The clue I received was from my sports medicine person who told me about belly breathing. I thought about my issues with my benchmark track workout and thought this was worth a try.

Yesterday I headed out to the track and decided to emphasize belly breathing. As soon as I took off the starting line, I would begin to breathe deeply through my belly, and not expanding my chest. I would also practice doing full breaths like this more rapidly. This allowed me to get to the end of my 10x400s and not be totally wiped out. Success!

So I sacrificed a little better profile view of my body for faster speed and sustaining a higher effort. Too bad. I’m still glad I’m improving and getting faster.

More on belly/diaphragm breathing at Wikipedia.