Back in 2011 when I first joined Launch Capital, we started a project to see if we could find untapped markets that would prove to be huge markets and produce huge wins but find them early enough so that we could get ahead of the wave and get our bet(s) in before everyone else figured it out.

While we are still working on ways to uncover untapped markets, one of the interesting things we have discovered is that when a startup appears heralding a new sector, it often is the only entrant for a long time, often for years. Then there is a trickle, and an exponential rise to flood.

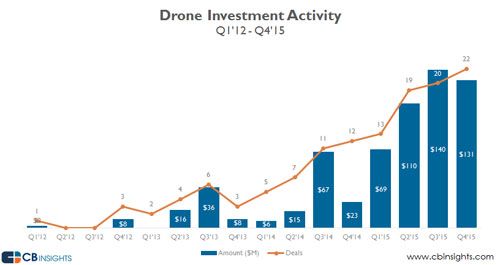

Take the Drone sector, for example. One analog for “hot-ness” of a sector is the amount of dollars investing into it. Here is a graph of Drone sector financing dollars from Q1 2012 to Q4 2015:

Source: CBInsights

Who was that lone drone startup who got funding back in Q1 2012? 3D Robotics, the very first funded drone company, co-founded by Chris Anderson, best selling author and WIRED editor. It was all about DIY back then. 3DR supplied UAV kits and seeded the first self built drones into the marketplace. Let’s call this the “First Contact Phase.” 3DR was around for a year before the next 3 were funded in Q4 2012. Let’s call this phase the “Trickle Phase” where a few more start appearing. It wasn’t until 2013 that a few more drone startups got funded, and then there was a lull until the 2nd half of 2014 when drones exploded into 2015. Let’s call this phase the “Flood Phase.”

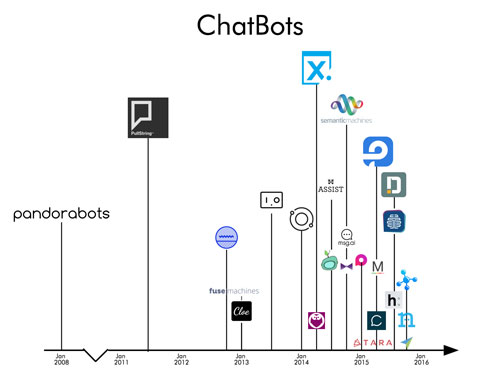

Here is a look at another sector: chatbots. We took a look at the chatbot industry and made a rough graph of startups across time (it’s a tough category because there are many working on bots, and many are working on it inside of other companies. We did our best pulling out those who are solely working on a chatbot):

The first startup appeared in 2008. Then things were very quiet for years until 2014, 6 years later, when things really started to take off. For startups, that is a long time to be surviving. It is possible that without industry and sector hype, there is suppressed availability for revenue and funding.

In either case, in the year before the main take off of the sector, there is a slow trickle of startups, and then it explodes.

When would be a good time to invest, for pre-seed/seed investors like us? Would it be better to invest in the First Contact Phase, or wait until the Trickle Phase happens? Or should we invest into the Flood Phase?

First Contact Phase

The most risky time to invest is when the first one that appears. You have the least evidence of a sector trend taking off at some time in the near future or happening at all.

For example, how would we know that drones or chatbots would take off instead of falling into obscurity or even death/dormancy until market conditions were more favorable? The first startup could try vainly to survive and die because they run out of money trying to create the market.

What drives an investment into a startup like this? It is through factors driven solely by belief. Belief in the entrepreneurs. Belief in shaky market factors that show little or no attraction to their products and services. Your own belief that this could be the next big thing. There is not much other evidence otherwise.

In theory, valuation would also be most favorable given lack of traction and sector trend evidence, although in recent years valuation variance at super early stage has not been all that much compared to others with traction and sector trend evidence.

Competition is non-existent by definition of being first, which does give this startup a unique opportunity to build the market without interference from any other companies.

Trickle Phase

A little bit less risky phase to invest in is investing in the Trickle Phase. You didn’t bet on the first, but now the second has appeared, maybe another few. Still the question remains – “Am I too early?” If you’re too early, some startups will die before the main wave appears; they didn’t raise enough money to survive long enough to catch the wave or were not able to get enough revenue.

In this phase, the market still questions whether these companies are viable and whether customers really want their products or not.

Valuation of these companies again may be lower than when the sector grows, but in today’s world, valuation may not differ much than in the First Contact Phase.

Competition increases as more startups enter the sector.

Flood Phase

And there is the Flood Phase: entrepreneurs, investors, customers, even media are all driving excitement and traction exponentially upward.

Sector trend factors are highest in evidence as many startups enter the field, and investors are putting a lot of money into them. Customers are trying out their products and services in hopes that they will gain the touted benefits.

Valuation marches upward as more conservative investors feel FOMO and must get in their bets on the trend or get left behind. Earlier startups who have managed to survive either First Contact or the Trickle Phase have gained traction and revenue, and later stage VCs invest in those, thus further motivating entrepreneurs to build companies in that sector because it is firmly hot. The media finally notices and posts are abundant about this new trend which adds even more fuel to the fire.

Competition is highest here as entrepreneurs build copycats to those who got funded before, and startups appear to tackle smaller segments of the sector. Investors who believe competition validates the market are validated!

Fast and Furious Acceleration into the Flood

As the title of this post suggests, it is amazing how fast a sector trend can move from Trickle to Flood. If you think about the overall sector I invest in, which is internet/mobile/software startups, it is easy to build something, too easy if you ask me.

When it becomes apparent that investors funding startups in a certain sector, other entrepreneurs also appear. In today’s world where accelerators are pumping out 100+ startups a year, and with the presence of media outlets who cover new startups, it is easy for someone to find a new sector to build something in, build it fast, and get out there for fund raising.

Investors are also self serving; they like to pump up the sectors they invest in for hopes that a Flood Phase will pick their own investments and drive them higher in value.

With software being so easy to write and with so many channels of public information, it basically takes nearly a year for a sector to enter and exit the Trickle Phase and explode into the Flood Phase. A year seems like a long time, but for investors it can take you by surprise. You see some hints, you process. You have conviction about some, you don’t about others. You make some bets, pass on others. If you’re an angel, you may be one of the ones saying “I love you but come back when you have a lead.” Now you’re waiting for other validation which can be slow in coming. By the time you get through all this, it’s already the Flood Phase.

Questions

The two essential questions to be answered for me are:

1. Which phase should we invest in?

I think that the phase you invest in is related to what kind of risk profile you have as investor (which makes sense) coupled with your belief and conviction about the startup and sector trend.

I’ve personally invested across all 3 phases. Of course, I’ve had more failures at the First Contact Phase where risk is highest. You make your bet and keep your fingers crossed. Looking back at my portfolio, the fastest growers have always been First Contact Phase investments.

My Trickle Phase startups have done well, depending on the circumstances.

I’ve made the least number of bets at the Flood Phase. I don’t like it when there is too much competition at the time of investment, especially at (pre-)seed. Valuation tends to be at the upper range which doesn’t work well with our fund economics.

For other investors, I think that later stage works best during the Flood Phase where it can be hard to pick the winner out of a large number of possibles, and it may be better just to wait for the winners to appear out of the noise. First Contact and Trickle Phases are better for investors who want to play in early stage.

The biggest accelerators are best positioned to see sector trends forming, as they see the most amount of startups through their applicants into their batch programs. They also see startups before the startup data companies do, because they only see startups AFTER a funding event happens. In addition, accelerators are often driving sector trends in the sense that they see something worthy of accepting and then media coverage of their demo days pushes new trends out to the public.

2. How do we find the next big sector trend?

This is the essential question that – well – can’t be answered for investors. Why? Because the answers are in the future! How can you predict the future? You can’t! HOWEVER, I think you can take some guesses and chances.

Whenever somebody appears working on something completely new, I look into it. If I never have heard of it before, I will immediately dive in. Unlike 99% of the other investors I’ve met, it is validating to me when THERE IS NO COMPETITION. If there is no competition, it is also possible that these guys are a First Contact startup in a new trend that hasn’t gotten too hot yet.

We’ve also spent a number of years looking into how to find the next big sector trend and, as you can imagine, it’s super hard looking for something that doesn’t exist. We are still trying!

Playing the market like an accelerator also helps; you must have enough conviction and resources to deploy investment broadly and be ok with a high error rate.

Many thanks to Julia Vlock for putting together the research for this post.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

The Importance of Revenue is Back

Back in 2009, shortly after the 2008 crash, I wrote The Importance of Revenue at Early Stage, Now More Than Ever. Up to that time, we had been on a roll – startup investing was growing well and we had bought into building traffic which allowed us to get to our next funding event. Then, the crash killed all that. Money was hard to come by, and investing in “momentum” or traffic only startups without much revenue was nearly dead. Only revenue generating startups were attractive to investors and a boatload of non-revenue startups died simply because they had none.

Then the startup funding environment came roaring back, we had our Instagram moment, and investing on momentum was in vogue again.

But times have shifted again. What has changed?

1. Tracking M&A values, they hang slightly above $20M [source: Berkery Noyes 2012 3rd Qtr Trends Report Online & Mobile Industry]. This is pretty low in general, and pretty unattractive from an investors’ standpoint when…

2. …Valuations for startups still hang around $6-10M cap or pre-money at early stage for the hotter deals, sometimes even higher. Remember that if you are to exit at the median, you must be doing pretty darn good and be above average. If you are not gaining traction, acquihires are happening at much, much lower values, definitely well below $10M.

Now to be perfectly clear, there are those out there investing on strategies that take into account 2-5X return on money. But our economics don’t allow us to do that – we need much more return.

3. Customers, whether consumers or B2B, are deluged by the exponential growth of startups and growth is harder to come by. In the near past, we used to tell startups that they needed 12-18 months to get to decent traction metrics; that quickly moved to 18-24 months, and now we think it’s 24-30 months. Wow! 24-30 months – this is a direct result of our observations on how startups are growing in the competitive marketplace, the battle for customers’ attention. When we saw them funded with runways of ~18 months or so, many needed more runway and so went to look for bridges, if they could not get series A – so we’re now at 24-30 months!

However, practically NO startup I know raises for 24-30 months at the seed stage – well, practically none. If you go to Techcrunch and other online publications that follow startups, you’ll see a ton of early stage raises at $1.5M-2.0M – what happened? This is smart. These founders, and their investors, have realized that they need more runway and have funded them for that. Startups who raise less than 24 months runway have a higher probabiility, now more than ever, that they will need additional runway to extend them to 24-30 months within a year.

But if you aren’t one of the startup darlings to get $1.5-2.0M at seed, what then?

4. Last, we’ve been in contact with some prominent financial guys who follow the economy like hawks. They process every bit of information that is out there, stuff we all can get and a ton of stuff that we can’t. (If there is anything I’ve learned about the financial industry, it’s this – there are those with the information and those without – those without basically include everybody else including you and me – and yes, the world will continue to have unfair information advantage no matter what we do with regulations). They are fearful that another 2008 is coming. We’ve been digging into this and have found evidence in a potential earnings cliff, and we are concerned as well.

All this means that we think the importance of revenue at early stage is back – one could argue that it never left, but what I mean is that it has risen to the top of the stack.

The world isn’t looking optimal for internet startup investing. That doesn’t mean there aren’t opportunities out there that can fit within the world we see right now – generating revenue is one of those key characteristics that can ensure some longevity even when the world is so uncertain. Once again, we look for that to bolster a startup’s chance for survival and give them maximal runway to achieve their next funding event.

Diversity in Investing is not Just a Cure for Internet ADD

I am often asked about how many investments I’ve made and I surprise them by the number I have made in such short a time. I too think I went out too fast as a budding angel investor but, looking back, I think ultimately this had many advantages, some of which were not obvious to me until I did it.

The obvious disadvantages are that I had allocated a portion of my personal savings to do this, and I ended up deploying almost all of it in 2 years! This unfortunately meant that I had to slow down dramatically the number of investments I do from now on, and potentially ratchet down the size of investment into new companies.

The obvious advantages of going wide are that you spread out your risk, just like diversifying your investments in your personal investment portfolio of stocks, bonds, etc.. Putting your eggs in one basket, or a few baskets, increases your risk of losing it all no matter what you put your money in.

The non-obvious advantage of going broad was the knowledge I gained from exposure to different companies and their personnel (and their personalities!), their products, their struggles and solutions.

I always knew I had ADD, and that I enjoyed working on multiple products. In my old position as head of user experience at Yahoo!, I could satisfy my ADD tendencies towards getting my fingers dirty in a variety of projects, and learning about many others. After I left Yahoo!, I wondered about how I would provide an outlet for my ADD-ness and orchestrated a solution through angel investing. By investing in many companies and becoming advisor to them, I was able to continue to satisfy my Internet ADD.

However, being exposed to so many products and projects also allowed me to see across many different products and be able to connect them in ways I would never have been able, had I not had access to the depth of information in each product. I was able to see synergies and feed my creativity, which allowed me to come up with ideas that would not have come to light without the broadness of depth of information (if that made sense). I had always been a big believer that creativity can be enhanced with more information (but also knowing that creativity can often be reduced because you get bogged down by knowing too much) and this was further proof of my belief. Working on one or two projects would never had given me the insight that I can see now. Also, if I was not advising and/or investing in these companies, I would not have gotten the depth I needed to be truly successful.

It was an non-obvious result of the diversity of my investments that I would be a more effective advisor to internet startups. My broadness of vision across many different products and projects means I can bring creative proposals to time starved entrepreneurs whose myopic but necessary focus on their own projects sometimes prevent them from seeing the wide view and potentially better alternative paths and solutions.

When the CFO leaves…

Sitting here at LAX, I read in this week’s Economist that George Reyes, CFO of Google will retire this week. Immediately, red flags arose everywhere in my brain.

A long time ago, I learned a valuable lesson which I believe to be true. Here it is:

When the CFO leaves a company, sell ALL your stock NOW.

My first encounter with this concept was when the CFO of Yahoo! left in mid-2000. At the time, all of us working there were still giddy (and incredibly naive) about Yahoo!’s prospects and that the stock price and all our fortunes would continue to grow unabated and unstoppable.

Boy were we wrong.

Smarter minds might have said that we could have read the signs, and that we should have been more realistic about the stock market and how high it could climb, and that the word “bubble” and its ability to “burst” should have been something we were watching for. Perhaps we could have crunched that data by ourselves, listened to the experts more carefully, and determined that maybe we should have gotten out before we lost everything…and then some.

In the midst of our giddiness, we saw our CFO leave the company and gave him a big party, wished him well in the creation of his foundation, and hoped that he could just play golf til the rest of his days.

And we all kept right on basking in our giddiness and our virtual fortunes and let it all ride. We let it all ride right down the drain in late 2001 when the market and Yahoo! stock crash landed big time.

That is, all of us except for the CFO who left and kept a huge chunk of the value of Yahoo! stock before it crashed.

Why would the CFO leaving be such a signal that it would be time to get out of a stock or not?

Here is why:

1. A CFO typically has tons of buddies in the financial world and has access to data, analyses, and information that you or I would never get hold of.

2. CFOs come from a career where all they do is think about money, how to make it, and how to keep it. Their analysis of the market is arguably in a much different place than those of us who don’t deal in money all day long. They are NOT going to haphazardly throw away money if they can help it and will bail at the first moment’s notice when they think they’ve topped out in an opportunity.

3. The letter “C” in their title means that have access to company information and analysis far more detailed and confidential than any of us can access. They can see if the company and/or the market is going sour long before you or me.

4. CFOs are master number crunchers. When it comes to money, they can do all this math in their heads far faster than we can with all the calculators and computers at our disposal. For sure, they will be able to calculate when their company and/or the market is going to level out or turn downward a lot faster than we can.

If a company’s prospects are flattening out or going downward, you can bet that the first person to take off and cash in his earnings will be the CFO. Staying on faith is highly doubtful; nothing personal, mate, but money is money and a money guy is not going to bet it on faith.

But if the company’s prospects are good, then why would a guy like the CFO leave?

So I hate making predictions but instead I’d like to offer up a hypothesis, with Google as a participant in this experiment. The hypothesis is, based on what I just posted here, that because the CFO just left from a company that has seen its stock go meteoric since IPO, Google’s prospects and growth have started to or will shortly flatten somewhat. This, in a market such as we live in, will basically trash the stock as the markets hate it when a company goes from super-growth to normal/consistent growth. Trashing the stock is something that CFOs can sense and that is why he is leaving in order to preserve his earnings in Google stock.

I wonder if my hypothesis is right? Let’s wait and see….!

P.S. To all my friends at Google who may be reading this post: I am sorry if I have such a dire outlook, but remember it’s only for Google stock, not the company. So don’t quit but SELL SELL SELL….

Comments Back Up, Movable Type was hosed

OK Comments are back up. My MT DB got hosed and I had to export everything and start using MySQL for the DB to help prevent future problems. Let me know if you see any issues…thanks for your patience!

Comments Busted

Sorry everyone. My comments DB is messed up. Let me try to fix this before anyone tries to post a comment…Thanks for your patience!

Wondering about Today’s Web

Welcome to my view of the world and how it relates to the Web of 2005+ versus that of 1995 when I started working on it.